After the Storm

Family, Interrupted - Conclusion

On a bright, clear Memorial Day in 2013, two months after my father's death, I stood at the bottom of our hilly Georgia backyard, grabbing up piles of dead leaves, pulled weeds, tree-killer vines, and blown-down branches.

With a full wheelbarrow, I pushed it up the steep hill to add to the mountain of dead vegetation waiting at the front yard curb. As I began to get forward momentum with the load, a worry hit. Had I pulled the backyard gate closed after dumping the last load? If not, Danny Boy, our oversized standard poodle, could have escaped and I’d spend the rest of the day running him down through our neighbors’ yards. All because of me and my distractable brain. Best get a move on.

Halfway up the hill, though, I stopped beside a large tree I’d planned to cut down this week. It lost root footing in an intense storm a couple of years ago and since then had developed the old tree slow lean, demanding support from younger oaks who wanted nothing to do with him and his old greedy sun-grabbing leaves.

Then again, I wasn’t sure. I’d liked this thick-trunked tree in its prime. But this last storm had only made things worse. “Yeah,” I thought, taking notice of my take-charge decisiveness, “I’ll get the chain saw on the way back down and get it over with.”

Wait. I shook my head clear. The dog and the gate. Four steps after grabbing the wheelbarrow and heading back up the hill, my heart started racing. I gasped for air. I set the wheelbarrow down again. There’s was no cardiac issue here; it was another panic attack. This wasn’t scary — it was irritating. I had these handled. I’d hardly had any during the terrifying months leading up to and after my sister-in law’s death last fall. Maybe because people needed me, and I was distracted from my favorite subject: me. But then this spring, the panic attacks came in unpredictable flurries. There was no rhyme or reason to the onset; you could be peacefully reading a book, or fuming as a movie on TV gets chopped into nonsense by erectile dysfunction and reverse-mortgage commercials. The solution is the same: deep breathing, conscious calm. Or last resort, Xanax. Not an excellent choice for a recovering alcoholic, especially one with chainsaw plans.

I could have taken a break, but no - I had to accomplish this. I had to push through my own bullshit. Do something worthwhile and visible. Our dog might have gone out the gate I left open. Hit by a car all because I was wasting time lost in self-obsession.

My heart still pounding, I shoved up the hill pushing the wheelbarrow, ready to face whatever disaster I’ve caused. But the gate was closed and latched. Danny Boy raised his head from the warm sunlit bricks on the other side of the patio to see if it was anything important. But it was just wild-eyed Frank, so he sighed and put his head back down. I unlatched, went out with the wheelbarrow, pulled the gate closed, and rolled toward the curb with the branches, leaves, and weeds.

My wife Margaret and my therapist said the panic attacks were part of my grief over my father’s death. That made sense in a way. I had loved him and spent my life with his intellect, courage, and strength as a model to build what I could out of my life. But for the three years after his brain injury, he had become a different man – often belligerent, uncaring, and weirdly sly. And because of that, I pulled away even as I helped care for him. His constant drinking clashed with my sobriety. His increasing dementia-fueled irrationality and violence had scared me witless.

I had done my best to help Mom and Dad navigate through his mental and emotional wilderness. But I feared I was being sucked into a dark passage of confusion, blame, and regret that was destined to be mine as well, one day dragging my own wife and children down with me. That didn’t sound like grief to me. At his military burial at Arlington National Cemetery, I felt grief for my mother and brother’s loss, not mine.

I blinked and realized I was standing next to the pile of yard waste at the front yard curb, staring blankly at the street like Boo Radley. I took a slow deep breath and let it out in a ten count. Going down this mental rabbit hole wasn’t helping me get the wheelbarrow unloaded. I slapped my hands together, grabbed the handles, leveraged the load on top of the pile, so I’d have room for the next, lifted the wheelbarrow down, and brushed out the last few leaves.

And Dad said, “Nice job, son.” For a moment I felt the same big hand on my shoulder that patted my back when I was twelve years old and stacked two cords of firewood behind the garage.

Rolling the empty wheelbarrow back toward the gate, I thought about the difference between Dad’s brain troubles and mine. His focus shifted arbitrarily, and he’d lose track of time and place. He’d had to repeatedly reframe reality, as he popped from the present day in Delaware to an ocean liner docked in France after World War II to a train taking him to Nebraska to see his grandmother when he was eight. Wherever and whenever he landed, all he wanted was to go home.

I stopped to look back across the front lawn at the mountain of yard debris at the curb to make sure it hadn’t fallen over into the street. The problem with my ADHD, I thought, wasn’t arbitrary shifting focus. It was the lure of over-active insight. Insight that pulled you under the surface into ever deeper perceptions and conflicting emotions. You concentrated so hard to either shake free or dive deeper into murky meaning that you forgot about yard work and anything else, and slammed into a memory that has perfectly preserved every sight, sound, smell, and touch.

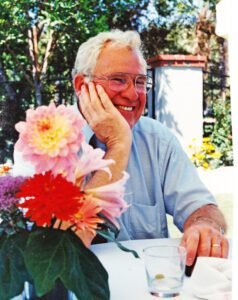

And bang - I was there with Dad in Delaware on Memorial Day the year before. The late afternoon sun filtered through his office window curtains. We had taken a picture together to email to his few surviving WWII Ranger friends, fellow D-Day veterans who climbed the cliffs under withering fire at Pointe Du Hoc. We were laughing, our arms around each other. He smelled of Lectric Shave.

Oh, great. Now I was Boo Radley in the front yard staring at the street crying. But stop, what was that five-foot-long branch doing in the middle of the lawn? I didn’t drop anything. I was crazy as a bed bug, but I kept my landscaping neat, damn it. Besides, well, branches don’t move. That’s when I noticed the birds screeching and swooping down, and the black head of the big snake reared up, flicking its tongue in my direction. I stood still, not sure what to do.

My first thought was to ask Dad.

From my memoir “A Chicken in the Wind and How He Grew”

An earlier version of this story was published on additudemag.com.